RI Public and Private Sector Compensation Comparison

Related Media: Report Finds RI Government Workers Out-Earn Private Sector (GoLocalProv), Guest opinion: Public employees would benefit from pro-growth policies (The Herald News), Tie the Public to the Private (GoLocalProv), Mike Stenhouse on the Helen Glover show (920 WHJJ); RI Owes $81 Million in Unused Sick, Vacation Time (GoLocalProv)

Download: Executive summary; full report with methodology (PDF)

Executive Summary

State and local government workers enjoy significantly higher compensation levels than their private sector counterparts, according to data compiled for Rhode Island as part of a national study conducted by economists William Even, of Miami University, and David Macpherson, of Trinity University.

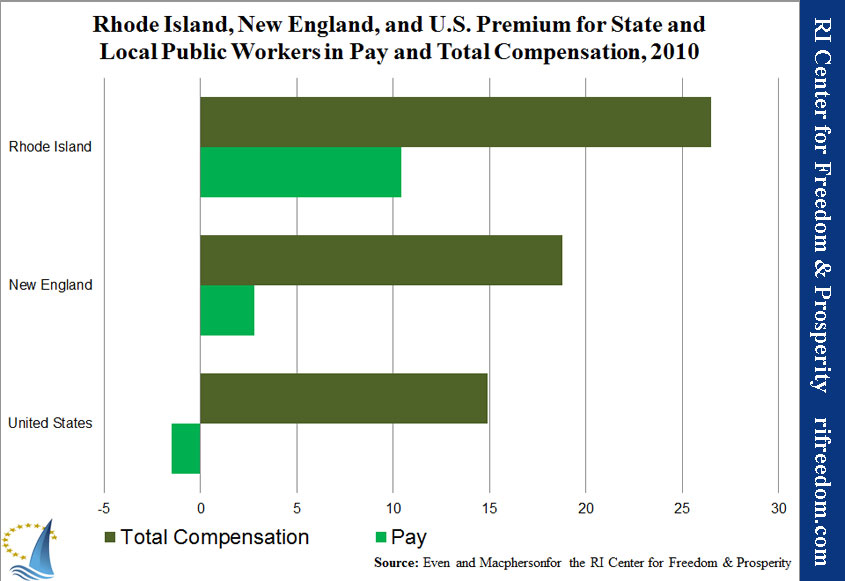

Even and Macpherson apply the most complete controls for such variables as education, experience, and broad job category and the most accurate accounting of benefits to date. They find that state and local government workers across the country receive a “premium” above their private-sector neighbors, but Rhode Island amplifies the difference:

- Rhode Island: 26.5% higher total compensation

- New England: 18.8% higher total compensation

- United States: 14.9% higher total compensation

Furthermore, a preliminary review of the effects of Rhode Island’s pension reform suggests that the changes to their retirement benefits did not appreciably reduce government workers’ advantage, only reducing the premium for government work to 26.24%.

Looking at base pay alone shows that job security and better benefits in government do not correspond with lower salaries, at least in Rhode Island and New England, where state and local workers receive:

- Rhode Island: 10.4% higher base pay

- New England: 2.8% higher base pay

- United States: 1.5% lower base pay

Averaging all jobs at every level, total public-sector pay and benefits in Rhode Island are competitive with Massachusetts and Connecticut, but private-sector workers earn nearly 25% less than their peers across state borders. Consequently, comparing averages within Rhode Island yields the following results:

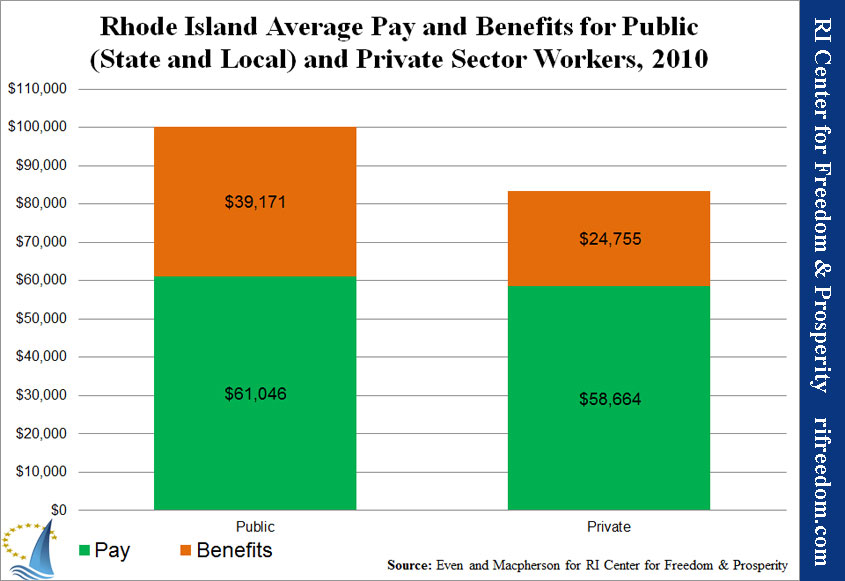

- Total compensation: 20% higher for government workers

- Pay (base salary): 4% higher for government workers

- Benefits: 58% higher for government workers

- Hours worked: 5% less for government workers

- Value of paid time off: 5% higher for government workers

Compared with the New England region, Rhode Island’s government employees are unique in having a higher average base salary than the private sector as well as a higher value for paid time off. They also enjoy a total compensation premium well above the regional average, even as they work the fewest total hours.

If there is to be any hope of keeping current compensation levels and benefit promises to government workers, the state must experience an immediate boom in the private-sector economy. Without rapid economic growth and a boost to their prosperity, taxpayers’ tolerance and capacity to pay for government beyond their means will continue to wane.

Data Analysis

Overall Averages

Rhode Island’s state and local government employees receive higher compensation than their private-sector neighbors by every measure, according a study comparing public-sector and private-sector compensation that the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity requested from economists William Even, of Miami University, and David Macpherson, of Trinity University.

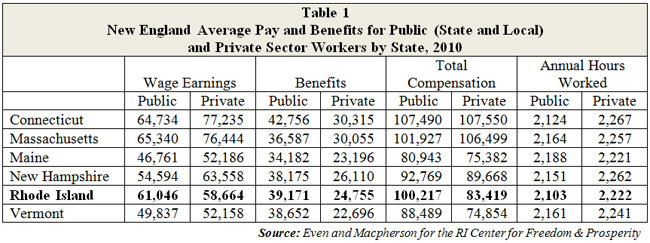

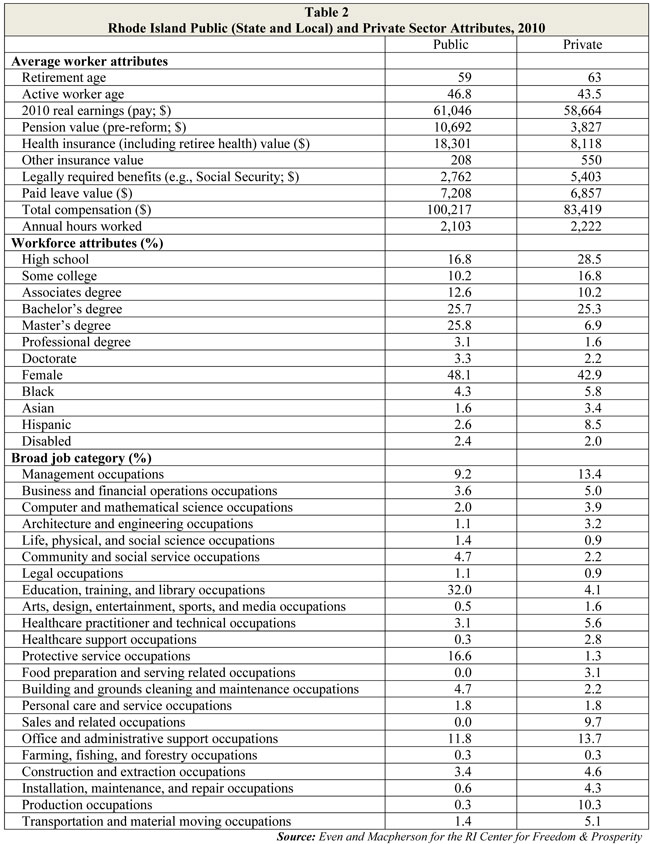

Chart 1 shows the average real earnings and benefits (in 2010 dollars) for state and local workers versus private-sector Rhode Islanders. Benefits take into account pensions, health insurance (including post-employment/retiree), other insurance, legally required benefits, like Social Security payments, and paid time off. The total compensation for the average public-sector employee in Rhode Island was $100,217, which was more than 20% higher than the private-sector average of $83,419.

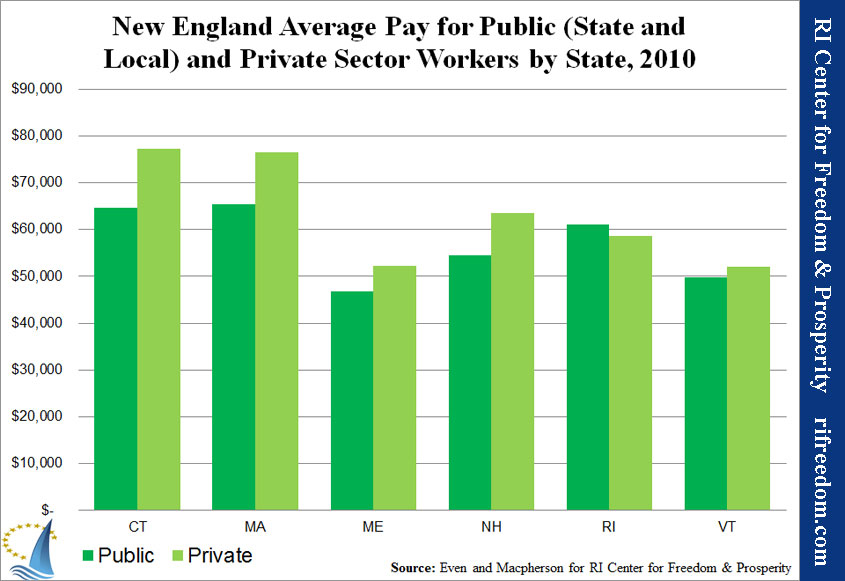

Rhode Island is inarguably in a high-cost, public-labor-friendly region, but even so, it is unique within New England. Chart 2 shows that Rhode Island is the only New England state in which the average wage earnings (base salary) of all state and local workers, on its own, was greater than that for all private-sector workers.

The most conspicuous reason for Rhode Island’s poor showing, here, is the huge gap between its economy and that of the two states that envelop it. While the Ocean State’s public sector is competitive with Connecticut and Massachusetts (with earnings only $4,294, or 6.6%, below the region-leading Bay State), its private sector has a $15,398 (23.3%) deficit.

Even when benefits are factored in, the private sectors in Massachusetts and Connecticut outstrip government employees. In contrast, Table 1 shows that Rhode Island adds a relatively large amount of compensation via benefits in its public sector and a relatively low amount in its private sector.

Another significant perk to working in Rhode Island’s public sector is time off. According to the data collected by Even and Macpherson, Rhode Island is the only New England state in which the value of the public sector’s paid time off ($7,208) is greater than the private sector’s ($6,857). (These numbers are included in the total for benefits.)

And while government workers in all New England states put in fewer hours than their private-sector neighbors, Rhode Island’s public employees put in the fewest. Moreover, only in Vermont is the gap between the sectors larger. (Note: Annual hours are calculated from weekly-hour responses on employee surveys.

Variable-Controlled Premiums

A common objection to such comparisons of average pay is that the types of jobs available within the public sector lend themselves to more-highly educated employees. Therefore, the argument goes, it is entirely appropriate for them to make more than the average of all private-sector jobs, because they skew toward the higher end of the workforce.

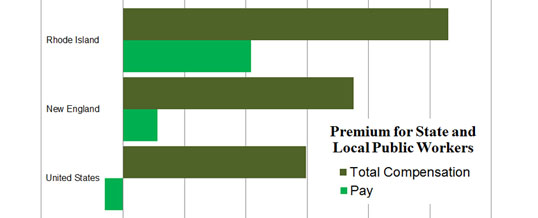

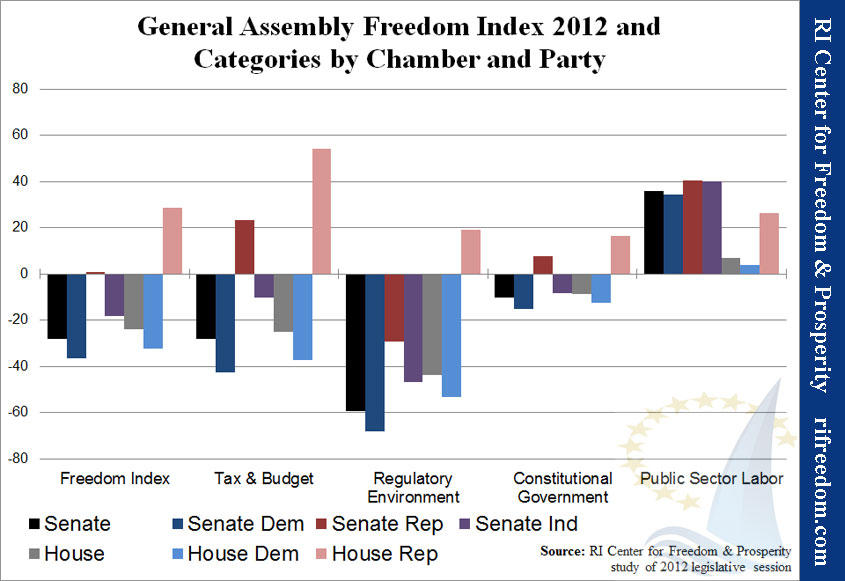

To investigate this explanation, Even and Macpherson performed a regression analysis for Rhode Island, the New England Census division, and the United States in order to compare similarly situated employees. Chart 3 shows a summary of the results.

The percentage shown is the premium for working in the public sector — that is, the percentage advantage in compensation from working in the public sector, taking into account employee characteristics (such as education and experience) as well as broad job category (such as management versus office and administrative support). (See Table 2.)

On salary alone, state and local employees enjoy a 10.4% premium in Rhode Island, even when controlling for other variables like education, experience, and broad job category. For New England overall, the premium is 2.8%. Nationwide, the public-sector actually has a salary penalty of 1.5% below the private sector.

Adding in the total value of benefits (before pension reform), Rhode Island’s state and local workers receive a premium of 26.5% over their similarly situated private-sector counterparts. That compares with 18.8% for New England as a whole and 14.9% nationwide.

A significant consideration that Even and Macpherson were unable to quantify due to a lack of data is job security. Given higher rates of unionization and the ability to affect their employers through political activities, government workers are generally understood to face less volatility than do private-sector employees. In theory, economists could apply a monetary value to that intangible benefit, but such an investigation would be beyond the scope of this study.

Pensions & Pension Reform

One important adjustment that Even and Macpherson have made to the raw compensation data is to determine the current value of pension benefits using a 4% discount rate. In a defined-benefit system, actuaries value the guaranteed level of income that employees will receive during retirement by assuming that investments will produce a certain return.

Rhode Island currently assumes a 7.5% return. Prior to the adjustment that spurred the 2011 pension reform at the state level, the assumption was 8.25%. Because this study uses data from 2010, that is the starting point for this data. By comparison, the average private-sector assumption is 6%.

In all cases, therefore, Even and Macpherson had to mark up benefit values to account for the likelihood that investment profits will fall short of predictions. It may seem counterintuitive that a benefit is worth more when invested money receives less profit. However, in the case of guaranteed pensions, the benefit is defined in the future, not the present.

Therefore, lower profits from investments would require greater payments by the employer, making the benefit of greater value to the employee now. In effect, the employer is promising a greater return to the worker than he or she would be able to achieve by investing on his or her own.

Because pensions make up 10-20% of the typical government employee’s total compensation, compared with 4-6% in the private sector, large reforms can greatly affect the premium that public-sector workers receive over the private market-place. For this study to be complete, therefore, some accounting of the effect of the Ocean State’s pension reform on the value of state employees’ benefit packages had to be included.

However, the imposing complexity of pension calculations is such that an accurate estimate of the reform’s effects would be well beyond Even and Macpherson’s scope. In particular, during the transition from the defined benefits pension to the newly developed hybrid plan, each individual employee’s benefit will be different, and results vary from job to job and across state and local governments. It will be a matter of years before accurate data is available.

Consequently, the public-sector premium given above can be considered the outcome if the lawsuit currently pending on behalf of the relevant labor unions succeeds in overturning the reform. For some sense of the result if the state prevails in its defense of the reform, the Center for Freedom & Prosperity asked Even and Macpherson to provide a rough calculation.

It’s important to note, here, that the pension data throughout this study assumes that all municipal employees are receiving the same weighted average contribution as those in the state’s two largest plans — state workers and teachers — with and without 2011’s reform.

Be that as it may, the effect of the reform on this study was relatively minor. The guaranteed payments provided through the defined-benefit portion of the state’s new hybrid pension system have gone down. But the state has increased the percentage of payroll that it must contribute each year, to make up for the 5% of their pay that employees are putting toward their defined-contribution plans. The state has added a 1%-of-payroll contribution to those plans, as well.

Consequently, the annual value of government employees’ pension benefit has only decreased from $10,692 to an estimated $10,476. In terms of the “premium” that state and local workers receive over similarly situated private-sector Rhode Islanders, the percentage advantage has decreased from 26.49% to 26.24%.

Policy Analysis

Living Beyond Our Means

When a family comes to a decision about purchasing any product or service, it doesn’t merely accept the seller’s sense of what’s reasonable. In addition to the market rate, consumers must take into account the quality of the thing they’re buying as well as their own ability to afford it.

With deteriorating infrastructure, doubts about the quality of government services, and the high-profile specter of unfunded municipal and state retirement liabilities looming over the state during this current period of economic stagnation, the compensation of public-sector employees has become a subject of heated debate about fairness and affordability.

Rhode Island is the only state in New England in which public employees have higher base salaries than the private sector. At the same time, state and local workers in the Ocean State work the fewest hours in the region. When benefits are factored in, Rhode Island has the highest premium for public-sector workers over private-sector workers, even if pension reform survives the lawsuit that unions have filed to overthrow it.

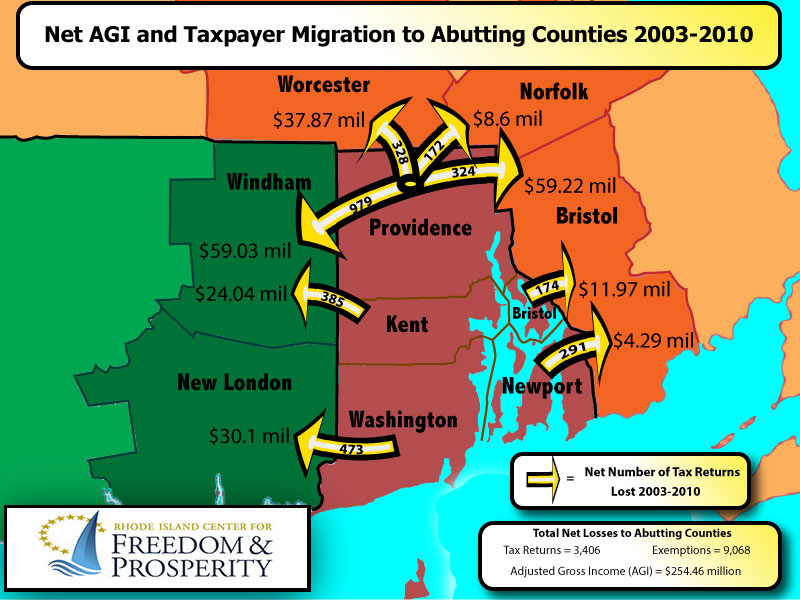

Meanwhile, the state’s economy is reeling, with arguably the worst employment picture in the United States, certainly the region. With dwindling taxable incomes and general economic activity, the state and its cities and towns will not long be able to continue to squeeze more revenue from a population that is losing ground economically and seeing many of its productive residents and college graduates flee to states with healthier economies.

Adjustments around the edges that do not take on the significant public policy issues we face will not be sufficient to turn the state around. Without rapid economic growth and a boost to their prosperity, taxpayers’ tolerance and capacity to pay for government beyond their means will continue to wane. Painful struggles between powerful insiders and the average citizen will worsen. Even more taxpayers may decide that the battle is not worth the benefits of living within the Ocean State’s borders.

Economic Growth Benefits Public and Private Sectors

With all of the emphasis on improving economic development in Rhode Island, there have been two conspicuous omissions.

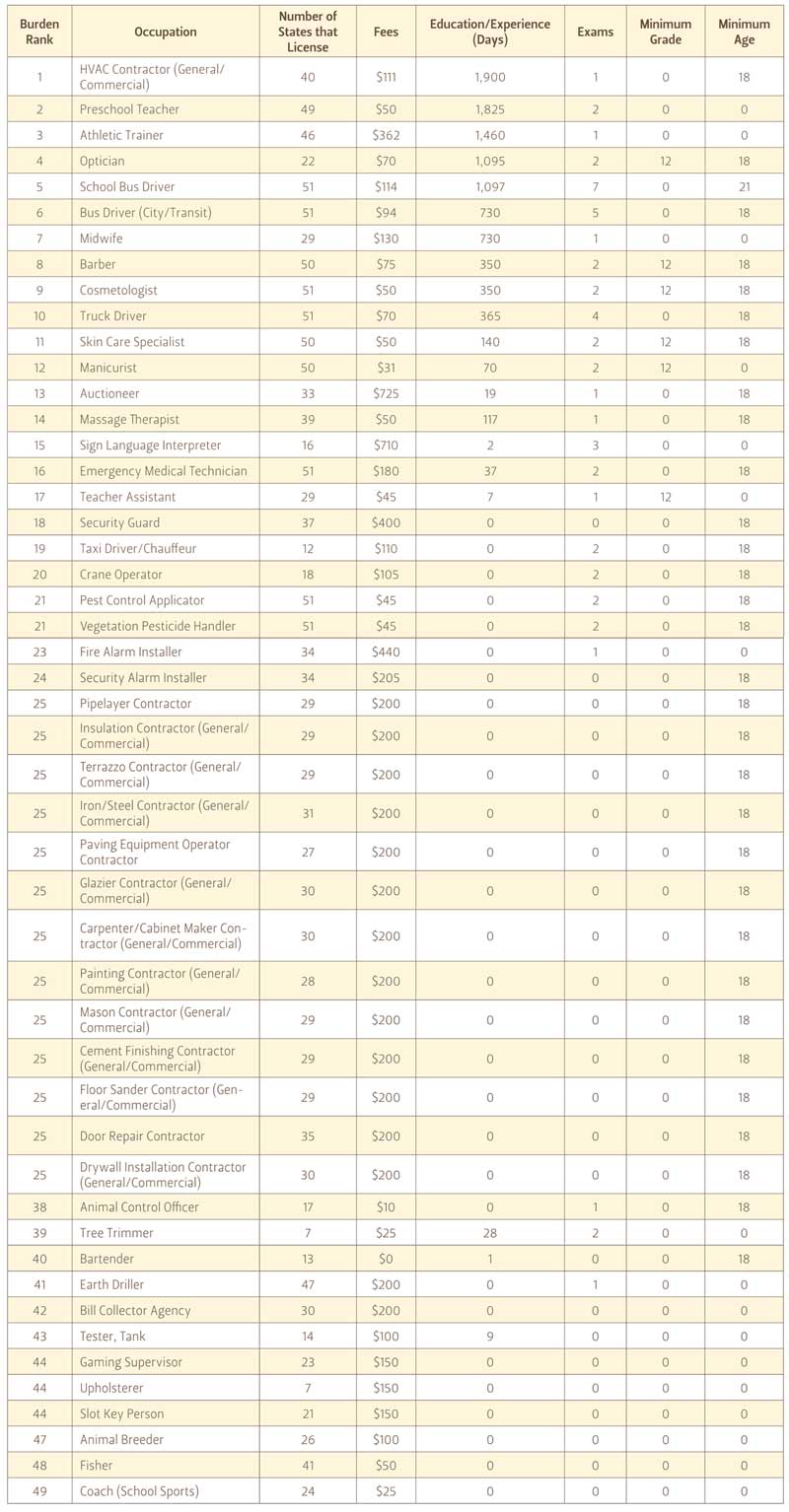

The first is the need for a complete change in the way that state and local governments treat taxpayers and businesses — as a matter of regulation, as a matter of spending, and as a matter of taxation.

The second, as emphasized in the data revealed in this study, is the fact that government workers should be out in front of the crowd advocating for change — not for tax-the-rich schemes that will never produce sufficient revenue, but for precisely the policies founded in economic liberty that will close the gap between private-sector Rhode Island’s earnings and those of its nearest neighbors.

If there is to be any hope of keeping current compensation levels and benefit promises to government workers, the state must experience an immediate boom in the private-sector economy.

Even the dramatic pension reform that sent unions to their lawyers and made state Treasurer Gina Raimondo a national policy star barely nudged Rhode Island’s public sector toward the national ratio of public-to-private workers. It hardly even brought the tiny Ocean State nearer to the average for the union-stronghold region of New England.

While additional compensation cuts and even deeper benefit reforms will be necessary in the public sector, the more significant factor in the public-private imbalance, locally, comes from the substandard economic conditions in which the Rhode Island taxpayer in the private sector is forced to survive. That is where dramatic improvement is most necessary, and most attainable, if public policy can be properly aligned.

Central Falls retirees discovered all too painfully that unsustainable compensation arrangements, whether salaries or benefits, are by no means guaranteed if obvious warning signs are not acted upon responsibly. The comparison of the public sector and the private sector in Rhode Island is one such sign of unsustainable compensation levels.

The people of Rhode Island depend upon government workers for the appropriate and necessary functions of government, but those workers depend upon the private sector to maintain a healthy economy and, in turn, sufficient government revenue. The top priority for employees on both sides of Rhode Island’s taxing and spending, therefore, should be reasonable reform that makes public-employee compensation sustain-able combined with the elimination of policies that restrain economic growth in the Ocean State.

Methodology

Download the PDF version of this report for Even and Macpherson’s full methodology.