Go to ConCon RI Home Page

The RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity commissioned a legal brief by the Stephen Hopkins Center for Civil Rights to determine if any constitutional language or case law exists that would impact the eligibility of a sitting elected official from running as a Constitutional Convention delegate, should voters approve ballot Question-3 this November.

Based on the legal brief below, the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity urges the special convention commission to recommend that the General Assembly, if and when a Constitutional Convention is approved, should establish a requirement that any currently elected official would first have to resign their current position before declaring their candidacy as a Convention delegate.

***

August 21, 2014:

The Prohibition of Service by Legislators and Other Office Holders as Delegates to a Constitutional Convention –

A “ConCon” Conflict

Written by the Stephen Hopkins Center for Civil Rights; commissioned and released by the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity

Summary: There is clear constitutional language and supporting case law that would prevent General Assembly members, and perhaps other state or local officials, from serving as delegates to a Constitutional Convention.

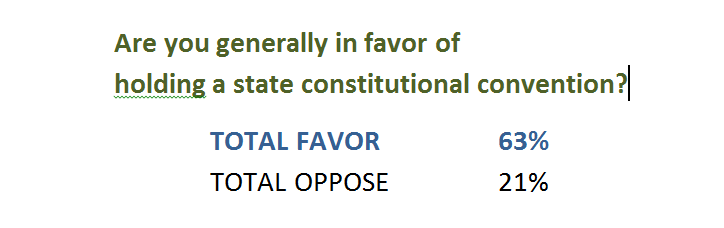

Background: This November the voters of Rhode Island will have the opportunity to approve or reject a ballot measure calling for a Constitutional Convention for the state.[1] While varied forces and interests are aligning around the question itself, one legal argument – who is permitted to run for convention delegate – is not only being raised but has also been the subject of a significant court case since the last Constitutional Convention was called.

In the 2009 decision in Felkner v. Chariho Regional School Committee [968 A.2d 865 (R.I. 2009)] the Rhode Island Supreme Court held not only that a specific statutory exclusion prevented a citizen from holding two public offices, but that “the simultaneous holding of these two positions violates the long-recognized common law doctrine of incompatibility.” [Felkner, 868.]

As with the statutory prohibitions in Felkner, the Rhode Island Constitution erects a clear bar to the holding of multiple offices in Article III, Section 6:

ARTICLE III – OF QUALIFICATION FOR OFFICE – Section 6. Holding of offices under other governments —Senators and representatives not to hold other appointed offices under state government. — No person holding any office under the government of the United States, or of any other state or country, shall act as a general officer or as a member of the general assembly, unless at the time of taking such engagement that person shall have resigned the office under such government; and if any general officer, senator, representative, or judge shall, after election and engagement, accept any appointment under any other government, the office under this shall be immediately vacated; but this restriction shall not apply to any person appointed to take deposition or acknowledgment of deeds, or other legal instruments, by the authority of any other state or country. No senator or representative shall, during the time for which he or she was elected, be appointed to any state office, board, commission or other state or quasi-public entity exercising executive power under the laws of this state, and no person holding any executive office or serving as a member of any board, commission or other state or quasi-public entity exercising executive power under the laws of this state shall be a member of the senate or the house of representatives during his or her continuance in such office.

This language clearly and unambiguously prevents General Assembly members from holding office with the Federal Government or that of any other state or country. Nor, it states, shall they “be appointed to any state office, board, commission or other state or quasi-public entity exercising executive power under the laws of this state.” [2]

While this later clause may seem at first to settle (in the negative) the question of whether a General Assembly member may serve simultaneously as a Constitutional Convention delegate, it could perhaps be read to apply only to those positions that relate to the executive power. And while a Constitutional Convention may (and likely would) in fact impact the powers and duties of, and limitations imposed upon the executive branch, it would not be unreasonable to view the Constitutional Convention as a body above all three branches, and a participant in none. If one preferred such a limited reading of the constitutional restriction found in Article III, then the next logical step in a legal analysis would be an assessment of the application of the doctrine of incompatibility.

In her opinion in Felkner, Acting Chief Justice Goldberg provided a clear roadmap to the question and a detailed history of the doctrine of incompatibility, its evolution, and the public policy that drives it. At its heart, the incompatibility doctrine is not a bar arising from the impracticality or physical impossibility of serving in two offices, but rather a bar against the inherent and unavoidable conflict that arises when “one [office] is subordinate to the other, and subject in some degree to its revisory power; or where the functions of the two offices are inherently inconsistent and repugnant.” State ex rel. Metcalf v. Goff, 15 R.I. 505, 506, 9 A. 226, 226 (1887), 15 R.I.at 507, 9 A. at 227.

After defining the relevant standard, the opinion in Felkner delves into the facts of the matter – the powers and purview of the two offices to which Felkner was elected – to determine whether service in the two offices would give rise to issues that “inevitably would result in the silencing of at least one of [his] constituencies.” [Felkner, at 874.] As with that case, there are a number of factors in the possible service of a General Assembly member as a Constitutional Convention delegate than implicate the incompatibility doctrine.

First, to put to a General Assembly officer the question of whether their powers should be limited or expanded at the very least draws questions of the appearance of self-interest and inherent conflict. At worst it creates clear and ethical conflicts if matters such as legislative pay, the shift to a full-time legislature, or other perquisites of office were to arise. And while some might argue that a recusal may suffice if such questions were to arise, the rare and important nature of a Constitutional Convention should in itself be an argument against such measures. Too rarely to the citizens have the opportunity to have their representative voices heard on matters of such import, and a system designed with the expectation that their voice may be silenced by the recusal of their representative delegate should be vigorously avoided.

Second, it is clear that the very purpose of a Constitutional Convention is the exercise of a “revisory” power over the structures that define the breadth and scope of legislative power as well as those of the executive and judiciary. An official who was elected by their constituents to exercise the powers of their office, could not at the same time be an advocate for the limiting (or expansion) of those powers. Further, the Constitutional Convention itself serves as a super-legislature, allowing the people, through this alternative mechanism, to check, balance and override the action or non-action of the General Assembly relative to specific issues of law and governance.

Finally, given the extensive entanglements of finance, funding, control, and oversight between the General Assembly and the municipalities of our state, a strong argument could be made that the facts of the matter[s] should extend the prohibition to any public official, whether state or local, not just General Assembly members. In addition to potential structural changes (regionalization, consolidation, shifts of control from state to local or vice-versa) practical administrative questions (such as those relative to school funding, approval of tax hikes, infrastructure, or the balance of powers between the state and its constituent municipalizes) are also very likely to present themselves. To argue that those local offices or programs that may be funded in large part by state revenues are not integral to the state executive function is to deny the modern reality of public finance. To assert that the decision making authority granted to the delegates of a Constitutional Convention to alter the scope of authority of local officials does not present a conflict if those local officials serve as delegates would fly in the face of the incompatibly doctrine.

And so, while some might hope that certain (or even a great mass of) current legislators might run for and take the oath of office as a delegate to a Constitutional Convention, thereby resulting in their effective resignation from the General Assembly, it is probably more beneficial for our democracy to make sure the rules are clear in advance, and let those who might have such an interest be aware that their service in one capacity will effect their resignation[3] from their prior hard won office. As importantly, the strong potential for a legal challenge to any legislator who attempted to serve in two capacities simultaneously would only serve to delay, demean, and complicate the process of convening a Constitutional Convention if called for by the voters of or state.

Therefore, we would call on those who may eventually be tasked with defining the qualifications and restrictions for our Constitutional Convention delegates to make clear the Constitutional, statutory, and common law restrictions discussed herein. As a practical matter, legislators should be prohibited from running for delegate seats without first resigning their elected office. A further exploration of who else might face a similar bar should be undertaken promptly, perhaps with appropriate anticipatory guidance from our courts.

Just as importantly, we would ask the General Assembly to consider (and take into account in the drafting of rules of election) the underlying public policy question and the impact of such conflicts, whether real or potential, on the gravity and import of a Constitutional Convention. To ignore this question would only muddy the process and add the expense of litigation, special elections, or other contests, and possible delay the Constitutional Convention itself.

The best and most prudent approach would be a clear legislative requirement that a candidate for delegate to the convention must first resign any state or local office before declaring as such.

***

End notes:

[1] ARTICLE XIV – CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENTS AND REVISIONS – Section 2. Constitutional conventions. – The general assembly, by a vote of a majority of the members elected to each house, may at any general election submit the question, “Shall there be a convention to amend or revise the constitution?” to the qualified electors of the state. If the question be not submitted to the people at some time during any period of ten years, the secretary of state shall submit it at the next general election following said period. Prior to a vote by the qualified electors on the holding of a convention, the general assembly, or the governor if the general assembly fails to act, shall provide for a bi-partisan preparatory commission to assemble information on constitutional questions for the electors. If a majority of the electors voting at such election on said question shall vote to hold a convention, the general assembly at its next session shall provide by law for the election of delegates to such convention. The number of delegates shall be equal to the number of members of the house of representatives and shall be apportioned in the same manner as the members of the house of representatives. No revision or amendment of this constitution agreed upon by such convention shall take effect until the same has been submitted to the electors and approved by a majority of those voting thereon.

.

[2] Interestingly, the perhaps most well know prohibition on political activity – the Hatch Act – may or may not prevent Federal employees from running for delegate slots in a Constitutional Convention. That act prohibits participation in

partisan elections, and so if the General Assembly were to structure the delegate races as

non-partisan, there may be an opportunity for participation by Federal employees.

.

[3] “It is well settled that, when a person accepts an office incompatible with one which he then holds, he thereby impliedly resigns or vacates his former office.” ; 3 McQuillin, § 12.67 at 367. Further, “[T]he mere acceptance of the second incompatible office per se terminates the first office as effectively as a resignation.” In explaining the premise upon which the rule of implied resignation is based, we stated that the resignation “can be thought of as one of election, though not properly one of individual choice. There is no room for an actual election, unless it exists simply in choosing to accept a second, incompatible office. Once that act is done, the law implies an immediate resignation of the prior office, accompanied by a surrender of all claim and title to that office.” Advisory Opinion to the Governor, 121 R.I. at 67, 394 at 1357. [Both referenced and cited in Felkner, 872,873.]