The Illusion of Public Sector economics

There is something important to keep in mind as we start down the path of debating pension reform in Rhode Island. It is perhaps not the most vital point in a debate where what really matters is “Truth in Numbers”, as Treasurer Raimondo puts it, but as a premise by which we frame the debate it is certainly worth noting.

The premise is that employees contribute to their pension plans. It is, in a very important way, false.

The premise is not unlike the related illusion that businesses pay taxes. They don’t. Not just in the Warren Buffet pays less than his secretary way. (Which is of course, baloney – he probably pays more sales tax on a dinner tab than the average secretary pays in income taxes in a year.) But rather, in the sense that corporations just pass through their costs to their customers.

It’s a failure to understand macro-economic concepts relating to the allocation of capital in a capitalist system that leads to this illusion. That may sound a bit high-brow, but really it just requires a bit of thought about human nature.

Imagine that you are going to invest in a business – perhaps you have $1000 in a 401k and you have to decide what stock to buy. You need to decide how much risk you’re willing to take and then look around to see what business will give you the best interest rate on your $1000 investment. Maybe you call an investment advisor to help sort it out.

That advisors job is to sift through the tens of thousands of companies out in the world and decide how risky they are and what return they generate. Since they can’t look at every company every time they need to get some advice, the market has created some short-cuts. Stock exchanges are probably the first layer of filtering. New York Stock Exchange listed companies have to be big and stable. The “Dow Jones Industrials” are an even more exclusive list of the power players.

There are other short-cuts as well. Things like “price-earnings” or “P/E” ratios give us an estimate on how much interest an investment n a company will pay. And different industries have different standards for where those P/E rations should be. Strong companies can pay out less interest because they are less risky. Speculative investments require higher interest rates to justify the risk.

So what does this have to do with corporations and taxes? Simply put, if you raise a tax on a corporation it doesn’t lower their earnings. They need to maintain the value of their stock, and that requires maintaining earnings. So what they do, along with all the other companies in their industry, is raise prices. So who pays taxes on Amazon, or Wal-Mart, or Big Oil? You do.

And what does this all have to do with pension contributions? It’s a different problem, but the same illusion. When a company “contributes” to an employee pension – say 50% comes from the employee’s paycheck and 50% from the “company” – it’s really just coming out of the employee’s pocket. If it weren’t for a variety of complicated and costly governmental carrots and sticks found in the tax code, the company would probable just as happy to give that cash directly to the employee. On their books “salary” and “benefits” are just two sides of the same coin. It’s what it takes to convince someone to spend eight hours a day on the shop floor or at a desk pushing paper.

In the end, the cost is the cost, and whether they pay it in the form of salary or benefits doesn’t really do much to impact their competitiveness. It may be convenient to have your employer pay for your dental insurance, or your retirement fund, or a disability plan, but if they told you they were just going to give you all that money directly – say a 30% raise – and you could buy it yourself, would that be a reason to turn down the job? Probably not.

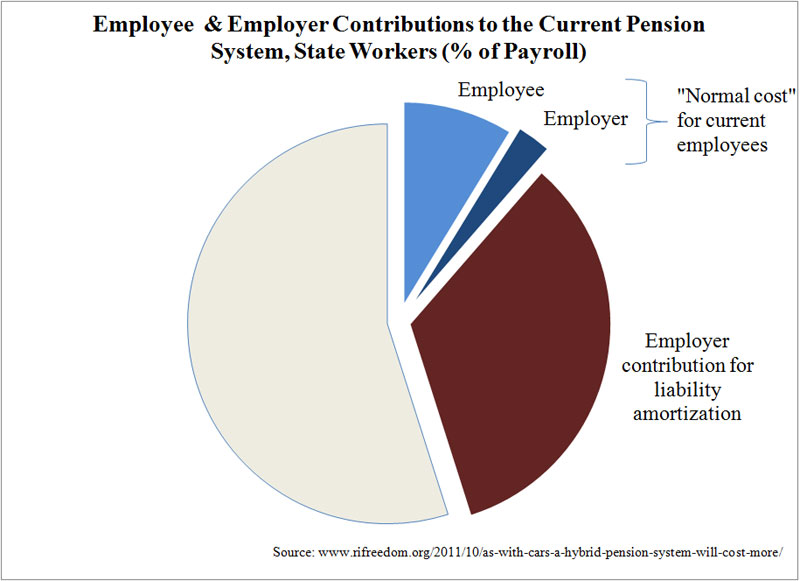

With public sector workers the same illusion applies. They don’t “contribute” to their pension, even if their pay stub shows two percent or 10 percent or whatever the split might be. That’s just a slice of the cost of employing that person.

The problem we have with public employee pensions is not how we allocate the split – whether it shows up as 90/10 or 10/90 on a government workers pay-stub, 100% of the cost is coming straight out of your pocket in the form of taxes.

So – that was all by way of a preface. Why I care about these type of illusions is because getting this basic economic perspective helps us understand the roots of the pension crisis. The crisis stems from lack of (1) market controls and (2) limitations on worker rights that prevent us from knowing how much that employee is costing us and where the purported “contributions” are going.

The market controls are those described above – in the private sector businesses need to maintain profitability or no one will invest in them. They can’t risk making promises without properly funding them because of market transparency. If investors discovered a multi-billon dollar unfunded liability in a company with only a few billion in revenues coming in each year, that stock would plummet. Since that scares the heck ot of investors they require all sorts of private controls lke independant actuaries and outside auditors.

With a government, there is no such control. Ratings agencies provide same level of oversight, and the voters technically have a say in firing the leaders who caused the mess, but in reality there are not adequate incentives for the people to provide their own oversight. In Rhode Island, as elsewhere, actuaries are ignored or written off as doomsayers. Worst of all, government finances are an impenetrable black box to most citizens.

The pension fund itself is another black box, and in effect it’s as if workers are not allowed to see what has been put aside for their retirement. There are promises of future payments of course, but since the money needed to keep those promises is not there when a pension system is not properly funded the retirees can only hope that the checks will show up each week.

Essentially the state has taken the pension money and frittered it away by not funding the pension system. If a private investment firm did what the state did somebody would be led away in handcuffs. In the private sector a retiree has the right to sue a trustee that was supposed to be managing their money in good faith. It’s an interesting legal question as to whether a state pensioner could sue state officials for breach of their fiduciary duty. The retirement board’s own actuaries have stated publically that the projected returns are more likely than not unachievable – they tell us that we have a 42.5% chance of seeing a 7.5% average rate of return, but they’re still basing our reform plans on that bad assumption. A 42.5% chance of getting the promised pension check? Is that a risk retirees should be happy with? My suspicion is that they expect odds somewhere above 90%, and if so they are not wrong to hold such expectations (And wold they be wrong to demand such certainty?)

Shouldn’t the retirement board be held responsible for placing workers pension checks at risk? If not, then what’s the point of calling them trustees?

In the end, we are the victims of these illusions. The pensioners of the state of Rhode Island and it cities and towns have been mis-led to by politicians and union bosses who knew what was going on. They had a view inside the black box, and told the workers who were relying on their professional oversight that everything was fine – that their contributions were earning interest and were adequate to fund a stable retirement.

Really it was a lie on top of a lie. The contributions were not made and the black box was just another insider’s piggy-bank.

***