Would Saving Superman be Kryptonite to RI’s Economy?

Opinion

Local developer Arnold “Buff” Chace of Cornish Associates and a Massachusetts real estate investment fund, High Rock Development, recently released a “redevelopment plan” for the property at 111 Westminster Street in Providence’s Financial District popularly referred to as “The Superman Building.” As the Providence Journal reports, the plan requires state-taxpayer-funded public subsidies of $39 million, $21 million in federal-taxpayer-supported tax credits, and up to $15 million in city-taxpayer-supplanted tax forgiveness in order convert a 441,000 square foot building from office use to primarily residential use.

$75 million … sound familiar? Given the disastrous track record of Rhode Island’s “public-private partnerships” of late, the Rhode Island Center for Freedom & Prosperity thought it might be appropriate to pose certain questions relating to the request. 38 questions, in fact.

38 Questions

1. Did we learn nothing from 38 Studios? With many multi-million-dollar years ahead of us to cover a failed gamble on subsidized video games, one would think that the state’s ability to adequately analyze this sort of massive investment and its risks would be a matter of suspicion.

2. Is this a priority for the state? Have we solved enough of our education, social services, and infrastructure problems to justify applying our treasure and attention to a massive, risky, and speculative real estate investment?

3. If we do have budget dollars to spare, why wouldn’t we invest them in infrastructure improvements that benefit all economic drivers? We can think of at least one bridge that could lose its looming tolls faster than a speeding bullet.

4. Do the voters responsible for this big check get a say as to whether they want to be in the apartment building investment business? Does their Constitution require their approval of such expenditures, or at least a legislative supermajority? (Should it?)

5. If you call it a tax credit, but you then let the developer sell it to other taxpayers, isn’t it just a really inefficient way of handing out a multi-million-dollar corporate welfare check?

6. Why do we need to involve tax credit brokers, anyway? It would be a lot easier to keep track of all the people who stand to profit if the money flowed out of the state check book? Or would transparency be like Kryptonite to the superpowers of the deal makers?

7. How about a tax-credit lottery? Tens of thousands of small businesses would love not to pay their full tax liabilities for a year or two.

8. According to the developer, 775 office buildings are in the City of Providence, representing over 15 million square feet of space. Do subsidies to one disadvantage the other 774?

9. For that matter, why not redirect the $75 million in subsidies to pay most of the first-year cost of the proposed elimination of the state sales tax? The Center’s Zero.Zero plan, currently before the General Assembly, would put that money in the pockets of every individual Rhode Islander and every business. That would spark new economic activity, not just moving dollars from one neighborhood or town to another.

10. Why can’t the developer phase in the conversion over time, using profits for additional remodeling? They project that “stabilization” of the downtown Providence office market will take 12 to 15 years, saying it would take 24 to 30 years if we don’t give them piles of taxpayer money (Advisors Inc. Economic and Fiscal Impact Study dated April 25, 2013 [HR&A], page 26). Cautious, phased-in funding over 5 to 10 years would achieve the same goal without the up-front risk.

11. For that matter, its own market study says that the Class A office market in Providence is seeing its lowest vacancy rate in 10 years and that midsize office suites could generate $25 per square foot in rent. Is that really not viable, or is it just harder to hide previous losses in smaller projects?

12. And while we’re at it, how can the HR&A report (page 30) claim that the “magnitude” of the project implies that the spending is “net new”? They seem to be arguing that 95% of the spending is “new to the region” because a project of this size “would not have otherwise taken place” without the taxpayer subsides. If Rhode Islanders have that much money lying around doing nothing, perhaps the developers should just take up a collection. Or maybe there’s a reason the project can’t gather funding without involving politics and taxes.

13. Why does the developer get to retain $15 million in declared value while arguing functional obsolescence at the same time? If you need this bailout to keep the lights on (literally), isn’t the building really worth nothing?

14. Is it somehow our problem that the owners paid too much for the building in the first place? In the nation’s 46th worst (of 51) real estate market, there are probably a lot of bad bets still shaking out around the state. Should other property owners start putting the word “iconic” in all of their materials?

15. The various “public-private” redevelopment successes touted by the developers in other states don’t seem to have required quite the same sort of taxpayer-funded cash in hand. Can they cite a successful effort that invested a similar amount of taxpayer money on a per-square-foot basis that wasn’t an investment in public infrastructure or funding traded for equity?

16. Did the building owners have an appraisal done when purchasing the building in 2008? They say they’ve spent $39,200,000 to date on the property. Since we’re being asked to make the same investment, shouldn’t we know their upfront purchase price, how much they’ve spent since then, what they were paid in rent over the years, and what they have taken out in management fees and profits?

17. Would a private investor get in league with someone whose own numbers indicate a loss of almost $25 million in five years on this project?

18. Who’s on the hook for the bad investment? Who invested the equity to allow the company to purchase the property, and who loaned them the money? Who are we really bailing out here?

19. More bluntly, does our proposed multi-million-dollar subsidy go to the new development, or does the plan include paying off old debt or old investors?

20. What is the tax value of the write-down to the developer and/or its investors or lenders? Will the state see the claimed $120,000 in corporate income taxes (HR&A, page 33)? Will the EDC exempt the sales tax on construction materials? Will the millions in federal payroll tax dollars that leave Rhode Island during construction be counted as an offset and a negative economic impact?

21. The report calls the proposed rate of return for investors “below market,” at 2–6%. So what exactly is motivating an investor to invest? Love of DC Comics–style architecture? Will there actually be other new investors, or will RI taxpayers be left holding Superman’s cape?

22. If we later find out that the money players who are already over their skis on the project are taking the reduced return instead of losing everything, would that be called “fraud”?

23. What kind of development fees, management fees, or other payouts to the developer, its investors, or its lenders are going to be made during the life of the project?

24. Specifically, what do we get for $3,105,678 in “legal & professional” fees and $3,342,050 in “administration & development” fees? (Would it be too bold to ask who exactly gets that $6,447,728?)

25. If it’s an investment, do we get equity? If the developer puts in $10,000,000 and we put in $40,000,000, do we get 80% ownership?

26. How can the developers claim that the $75 million will drive economic activity without subtracting the $75 million that taxpayers will no longer have? Simply taking it from us and spending it yourself does not yield new economic activity. A better term than the repeatedly used “generate” (HR&A, page 2, for example) would be “relocate” (or perhaps “redistribute”).

27. Who thinks it is a compelling argument that the project will save $740,000 in lost property tax revenue over the long term? The subsidies amount to roughly 100 times that amount. If we took those tens of millions and simply lowered the commercial tax rate in the City of Providence and across Rhode Island by eliminating the two-tiered tax system that today punishes and drives out businesses, it might lead to new tenants downtown and push up property values and assessments.

28. In the absence of such market forces, where will the anticipated tenants come from? Won’t they just leave the suburbs or the neighborhoods and move to the subsidized building? Which cities and towns will lose the professional residents the project intends to attract?

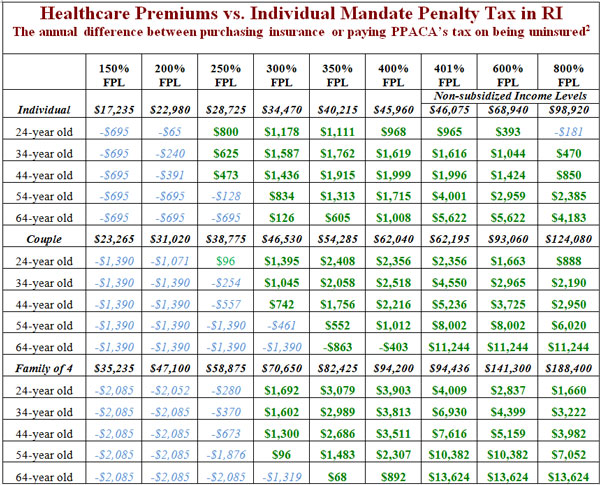

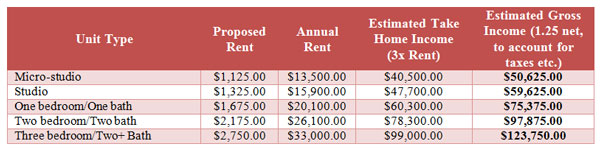

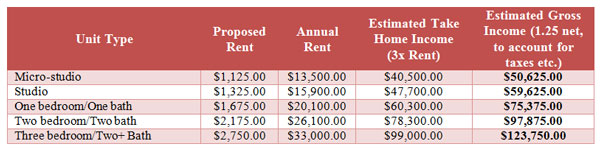

29. Who’s going to get those Burnside Park views? The developers’ “tenant profile” talks about “young professionals, older professionals, Boston commuters, empty nesters, and students.” Not exactly those most in need. This table of expected annual incomes for each unit type assumes that housing costs represent about one-third of take-home income. In that case, our average beneficiary is making around $75,000 per year.

30. Is welfarequeenus hipsterus a rare breed of urban parasite noted for its aversion to suits and Windows-based products and its keen sense that everybody else can afford to pay a bit more for their greater good?

31. Man of Steel aside, if we’re subsidizing “stainless steel appliances” and “granite kitchen and bathroom counters,” can we leave our doggie bags there when we go out for a night on the town after dinner? How about using the “24 hour fitness center” and “24 hour concierge/security”?

32. Given the roughly $75 million in total proposed handouts, the proposal amounts to a subsidy of about $200 per square foot for 265 new households (HR&A, page 34.) That kind of money builds a nice house; how about we just build a bunch of those and give them away? That certainly seems more equitable than subsidizing one tall building in a single bound.

33. How can they characterize a projected 104 jobs as economic growth? Aren’t the people who will live there economically active today? Same goes for resident spending estimates (HR&A, page 36.) Even if every resident moved here from out of state, the HR&A study (page 38) only projects $697,000 in annual revenue to the State of Rhode Island, for which it calculates a net present value of $8,600,000. So we invest $39 million in cash, and another $36 million in incentives, and we know on day one that over $60 million of that subsidy is a write off? Wouldn’t it be a better investment to spend $105 million to eliminate the sales tax and clear a path for 25,000 jobs?

34. How can they claim a “multiplier effect” from jobs that are presumably mostly here already? The “IMPLAN” model (HR&A, pages 41–43) for estimating economic impacts and multiple effects is certainly respected and credible for its purposes, but the HR&A study utterly misuses it. The IMPLAN model assumes new economic activity, not simply the shifting of resources within the state; that’s more like a TRANSPLAN.

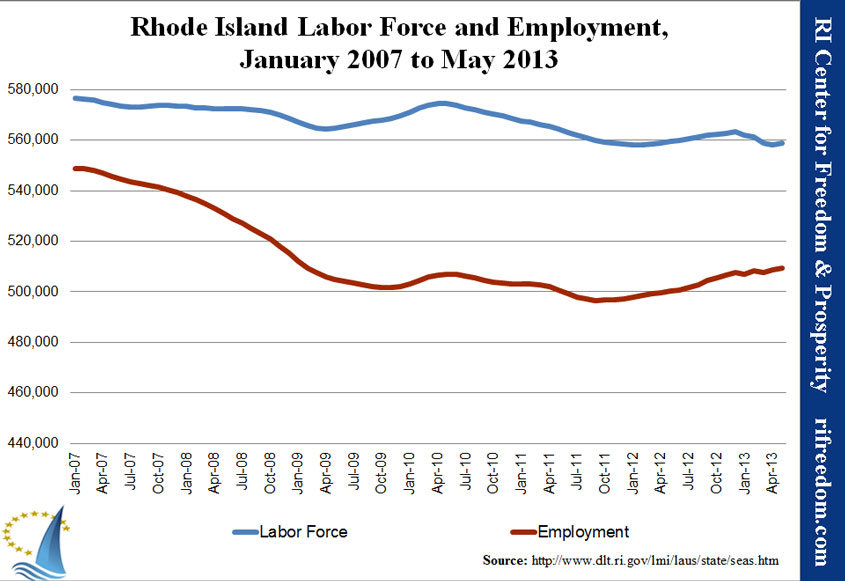

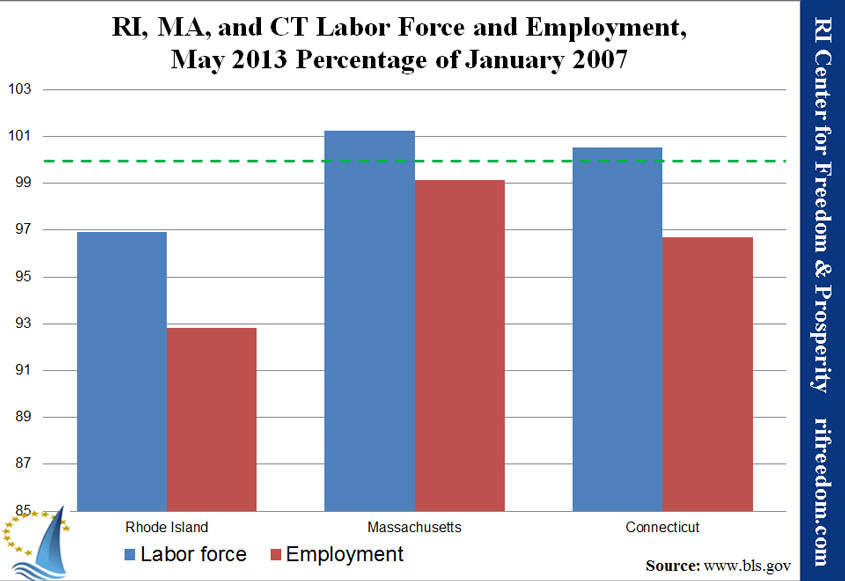

35. Are we crazy to think that myopic economic analyses, absurd corporate welfare handouts, and inept economic meddling contributed to the fact that “Rhode Island’s economy suffered more from 2008 to 2012 than the neighboring New England states,” as the developer’s market study puts it?

36. Mightn’t a broad-based reform help replace the roughly 1.5% population loss the study anticipates for the state with population and economic growth? As the developers’ own analysis notes, we have 35,900 fewer jobs in Rhode Island today than we had at the peak of 2006. Take out the 112,000 largely government funded healthcare and education sector jobs, and the 49,700 or so public sector jobs (U.S. Census Bureau 2011 Data for Full Time Equivalent Employment, state and local), and our current private employment of 388,000 is around 10% below the peak.

37. If this deal ends in disaster, and taxpayers lose again, do we at least get the consolation prize of watching some political player get banished to Krypton?

38. In the spirit of Rhode Island’s economic development habit of ending up where it began, we’ll close with: Did we learn nothing from 38 Studios?

On a Serious Note

Many years ago, the EDC liked to talk about “traded services” as the types of activities that represent economic growth for a state. They are not activities that occur simply because of their proximity to the local market. For example, a restaurant is not a traded service, because people will not travel to South Carolina for dinner. On the other hand, jewelry manufacturing is a traded service, because another state can provide incentives or an economic environment that would draw that business away.

It follows that economic development policy should be focused on activities that are portable, or traded. To subsidize non-traded services is simply to shift resources from one pocket to the other, while dropping a few dollars on the ground in costs and expenses.

Moving a Rhode Islander from Pawtucket to Providence is economic activity, but it is not economic growth. The same can be said for the new dry cleaner or coffee shop that the resident will now frequent. The construction activity for a new Providence apartment may be simply offsetting the same type of construction activity back in Central Falls.

Except that Pawtucket, Central Falls, and the other cities and towns in the state will never know what might have been.