NEW! Pension Open Government website: RIOpenGov.org

Go to RIOpenGov.org – our new, interactive website with searchable & sortable data displays for 26,500+ RI pensioners

Go to our Pension Reform page – pension reform updates, meet our nationally recognized special pension “task force”

Media Release

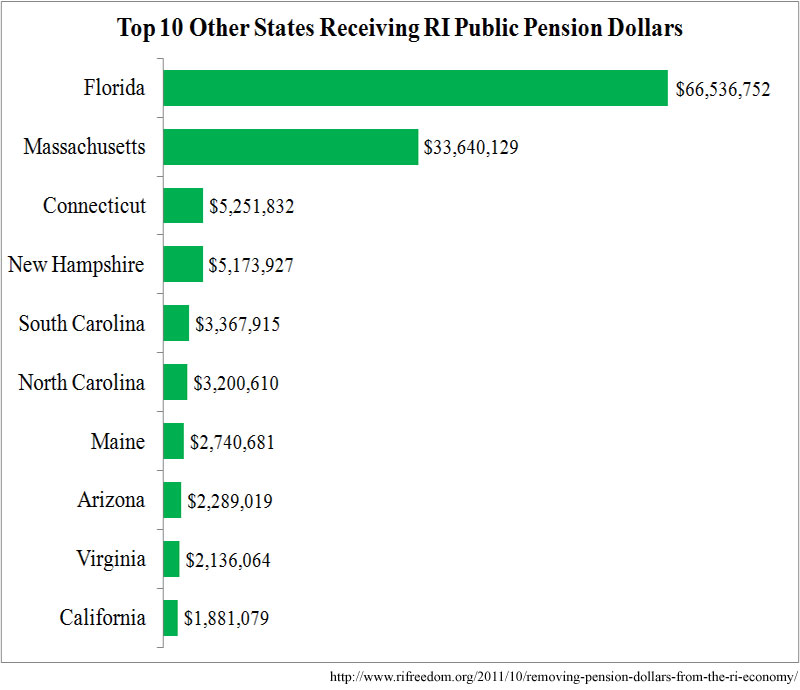

October 27, 2011, Providence, RI – The Rhode Island Center for Freedom and Prosperity today launched a new ‘open government’ website that adds new information to the current pension reform debate in the Ocean State.

The website, www.riopengov.org , is an interactive online database of state public employee pension data for current retirees. The data, which can be viewed in both table and graph modes, was provided by ERSRI (the Employees’ Retirement System of Rhode Island) through an open records request.

The information for 26,500+ pensioners can be sorted or searched by employee name, retirement year, benefit type, benefit structure (group), state of residence, and disability type. The website shows base annual pension as well as the COLA benefits for individuals or groups of individuals. The website was created by Visible Government Online, a 3rd party vendor to the RI Center for Freedom …

Read the full Media Release here

More Municipal Pension Systems Soon to be Included on RIOpenGov.org

The following municipal pension systems are not included in our current RIOpenGov.org website. An ‘Open Records’ request has been sent to each city and town. Check back for status updates regarding receipt of the requested records.

WARWICK: Warwick Police and Fire Pension Plan I, Warwick Police Pension Plan II, Warwick Municipal Pension Plan, Warwick Public Schools Employees Pension Plan, Warwick Fire Pension Plan II – limited manpower, may only be able to provide limited data without charging major fees (no other state or municipal entity has suggested fees for this inromation).

NEWPORT: Newport Police and Firemen’s Pension Funds – received only some of the data we requested. Determining now how to incorporate with more complete data.

CENTRAL FALLS: Central Falls Police Pension Fund – no response

CRANSTON: Cranston Police and Fire Employees Pension Fund – has requested a 20-day extension. Data expected in mid-November.

PROVIDENCE: Providence Employees Retirement System – initial internal confusion as to who to direct the request to.

EAST PROVIDENCE: East Providence Firemen and Police Pension Fund – has requested 20 day extension. Data expected in mid-November.

WEST WARWICK: West Warwick Town Pension Plan – no response

WESTERLY: Westerly Police Pension Fund – data expected by early November.