How Easily the Hybrid Pension Reform Can Be Undone

In his Sunday Providence Journal column, Assistant Managing Editor for business, commerce, and consumer issues John Kostrzewa describes the business community’s enthusiasm for the just-passed pension reform:

There was a lot to celebrate because many of the 700 businessmen and women who attended the [Providence Chamber of Commerce] dinner had contributed their money, influence and support to back the reform effort that had been heavily opposed by the labor unions. It showed that when the business lobby is committed, organized and focused, it can be a potent force in setting public policy.

Myself, I continue to be skeptical that the field broke so cleanly into opposing sides. That is, I’m not so sure Business faced Union and won a battle, with pension reform.

A few years ago, during teacher contract negotiations in Tiverton, National Education Association Rhode Island Assistant Executive Director Patrick Crowley put forward a proposal for health savings accounts — which are typically seen as key components of serious conservative healthcare reform plans. A close look revealed that the union’s plan was constructed in such a way that the reform would hardly have saved money, yet it enabled negotiators to proclaim savings with the health benefit so as to argue for other increases, as in salary. The lesson that stuck with me is that unions are willing to seize on the trappings of reform, but they’ll, first, force reformers to negotiate something, like raises, in order to insert their favored concepts into a contract and, second, work to dilute the effect of the reform of itself.

General Treasurer Gina Raimondo has successfully brought the notion of a defined-benefit/defined-contribution hybrid to the Rhode Island public-sector pension system, but reformers arguably didn’t do enough to ensure that it would be a strong win, and it’s beginning to look like other concessions made in the process may very well outweigh the improvements. The new 5.5% privatization tax that the General Assembly imposed on state (and perhaps municipal) government was likely a mere first taste, especially if NEA-RI President Larry Purtill’s exhortations are any indication.

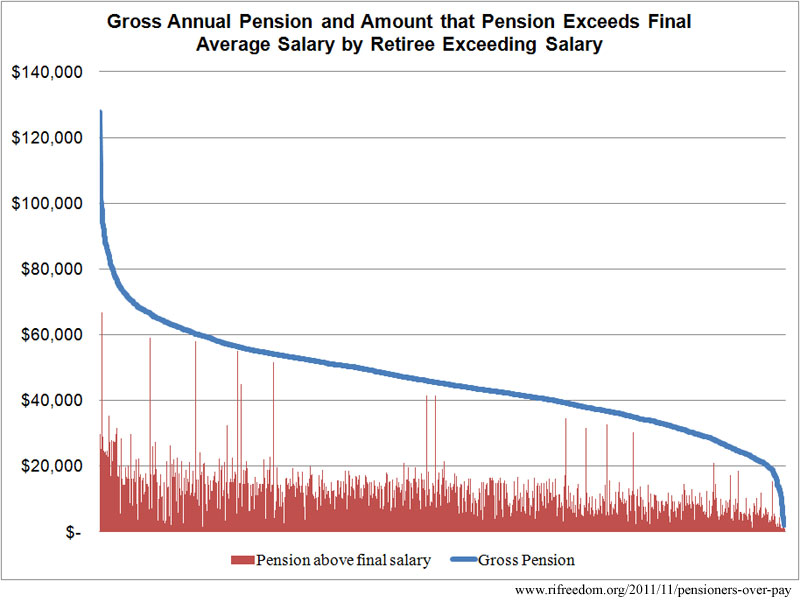

The quantitative question that naturally follows such predictions is: Just how much would it take to undo the benefit of a reform like the hybrid system? Well, for starters, I’ve already pointed out that the hybrid benefit is more costly than the defined-benefit system alone, if the actuaries’ investment assumptions hold. Regardless of investment returns, however, it won’t take much at all for the unions to negate the “hit” that they’ve taken with the hybrid through advantageous policies in other areas. If legislators and other government officials seek to mitigate the backlash from the unions by offering such juicy concession prizes as the privatization tax and binding arbitration, the reform could easily turn into a recidivistic windfall for public employees.

For example, if we assume that the average teacher will work for 25 years and retire for 20, the unions will only have to increase the average annual raise by 2.76% to leave their members retiring with exactly the same defined-benefit pension. In other words, if teachers’ typical annual raise is 4% (which is the state actuaries’ assumption) and the unions bring that up to 6.76%, a 25-year teacher will see no change in defined-benefit pension whatsoever.

For state workers, the necessary delta is 2.73%. For teachers and state workers who stay on the job for 30 years, which will be much more common, given increases in minimum retirement age, the delta to erase the effects of the hybrid reform is 2.5%.

That doesn’t tell the whole story, obviously. Most important, if the unions manage to procure higher salaries for members, then the reward far exceeds the increased pensions, as employees bring home more money each year of work. The hybrid plan also lowered the amount that employees contribute to defined-benefit portion of their retirements, which provides 5% or more in annual savings for them, and added a 1%-of-payroll employer payment into the defined-contribution portion, which amounts to a 1% raise deposited into a high-yield savings account for future use. On the other end of the scale, one has to factor in variations in cost of living adjustments (COLAs) based on the size of base pensions.

Taking all of those variables into account, a teacher who works for 25 years and retires for 20 only needs his or her annual raise to be 0.89% higher than it otherwise would have been in order to completely eliminate the adverse effects of the hybrid reform over the course of his or her career and retirement. If he or she works for 30 years and retires for 15, that delta drops to 0.68%. For state workers, the parallel numbers are 0.92% and 0.71%.

That is, if the expected 4% annual increase in teacher pay becomes 4.68% based on concessions to the unions, the combined compensation from salary and pension will exactly equal what it would have been had the hybrid reform and the concessions never occurred. Keep in mind that this doesn’t include the five percent of salary that employees will be putting in their defined-contribution plans or the investment yields from those plans, from both employee and employer contributions.

Of course, it will be all but impossible to tell whether this effect was actually obtained. The economy might force the average annual raise for state workers down to 3%, but if, for example, the privatization tax prevents the pressure of competition from driving it down to 2%, then public workers would have ultimately benefited from wave of reform. (And, yes, it’s tautological to note that taxpayers would have lost out.)

If the business community really does have pull at the State House, then it ought to apply its strength to resist any additional giveaways that legislators are planning to offer unions to buy forgiveness of their pension votes. Next it ought to strive to repeal the privatization tax as well as the provision of the pension reform that puts future adjustments in the hands of the union-heavy Retirement Board. Otherwise, any celebrations over the General Assembly’s 2011 special session on pensions will soon prove unjustified.