Minimum Wage’s Cost in Jobs: 432 at $8.25 and 3,466 at $10.10

Profile of minimum wage worker is NOT of a low-income, family bread-winner.

Related Links: WJAR-10 TV Story; GoLocalProv Story; Pew Research Center: national data backs up our findings; CBO – nonpartisan federal agency echos job loss projections (2014)

2014 Wall Street Journal story confirms Center’s position

Video by FEE: The Truth about the minimum wage …

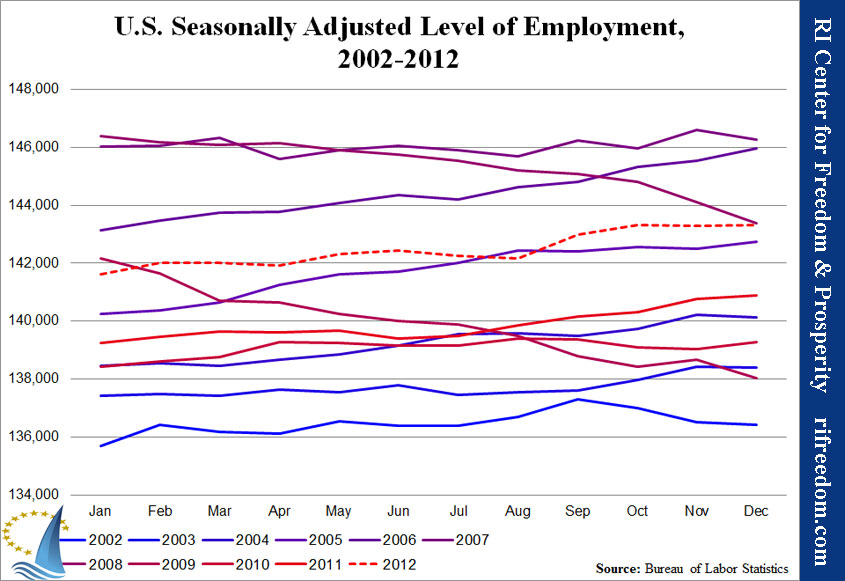

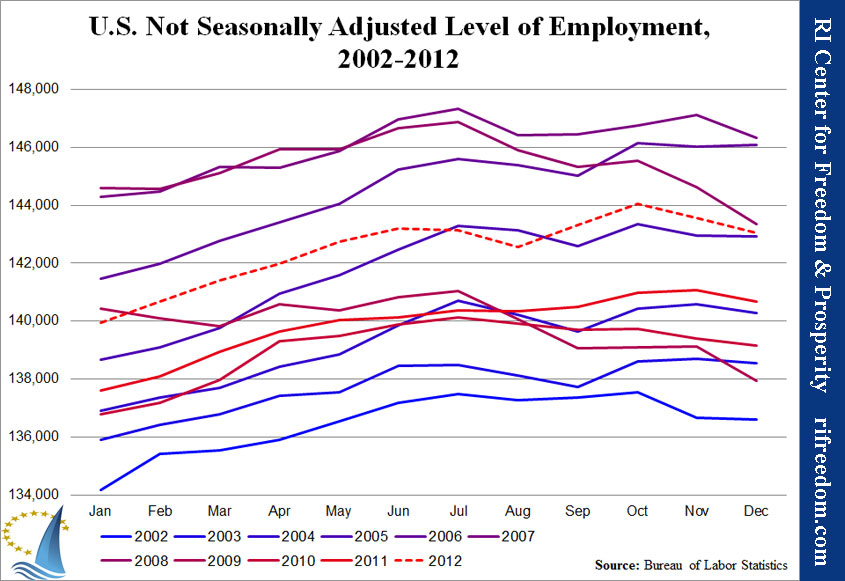

As an update to prior studies of the effect of increasing the minimum wage on Rhode Island’s employment situation, the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity estimates that proposed increases could cost the state hundreds or even thousands of jobs.

Legislation passed the General Assembly in 2014 that will increase the minimum wage in 2015 to $9.00 per hour, from its current $8.00, which was itself a new increase from $7.40 2 years ago. When all is said and done, this jump from $7.40 to $9.00 will wind up costing the state hundreds or thousands of jobs, the lion’s share affecting teenagers.

Additionally, legislators in the U.S. Congress are advocating for an increase to $10.10 per hour or higher. That change, we estimate, would destroy 3,466 Rhode Islanders’ jobs.

Minimum Wage Changes in Rhode Island

The very next session after the Rhode Island General Assembly voted to increase the minimum wage from $7.40 to $7.75, the legislature will consider bills moving it up again, to $8.25. The elected officials who made H5079 and S0256 among the earliest legislation to hit the State House, this year, surely see the move as a campaign to help struggling families. But the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity sees it as a continuing assault on the state’s economy and especially those most in need of upward mobility.

Last July, the Center found that Rhode Island’s move from $6.75 to $7.40, from 2005 to 2011, likely cost teenagers in the state 397 jobs. The increase to $7.75 destroyed an estimated 200 more.

Based on the work of the economists who performed that study, David Macpherson (Trinity University) and William Even (Miami University), with a review of the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey for 2011 and 2012, the Center estimates that, overall, the move from $7.40 to $8.25 will eliminate 432 jobs, 204 of them among teenagers.*

Who Is Affected?

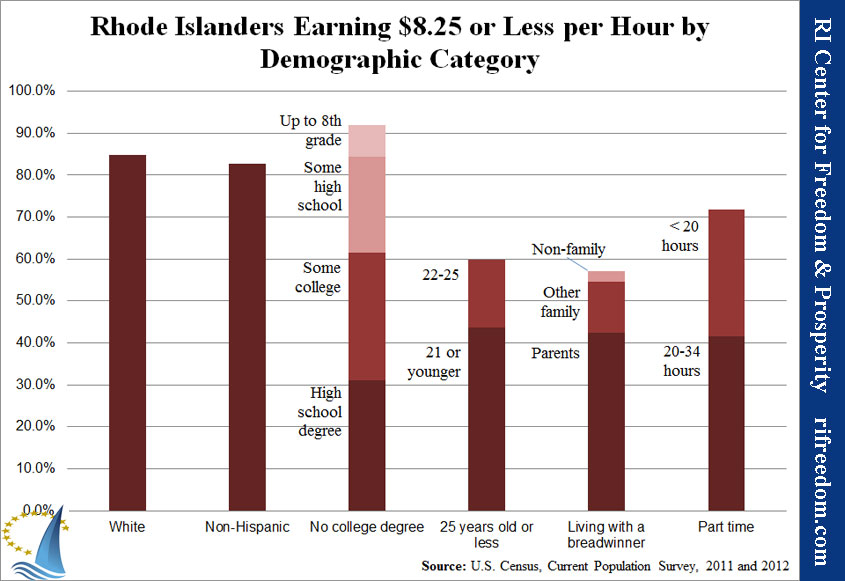

According to the study, 24,846 Rhode Islanders currently have jobs that pay them at a rate of $8.25 per hour or less. The “typical” profile — using the highest percentage by each demographic quality — is of a white non-Hispanic high-school graduate, 21-years-old or younger and with no college experience, who lives with his or her parents and works 20-34 hours per week. The following chart shows how dominant each of these qualities is in the under-$8.25 population.

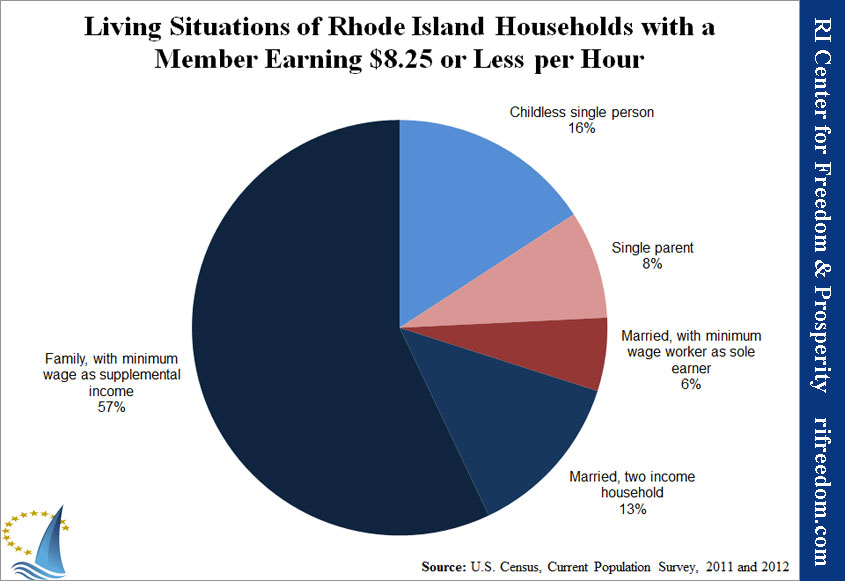

Simply put, the image of low-income families struggling along at minimum wage is mostly false. The average family income of Rhode Islanders who make $8.25 per hour or less is $61,299. For these families, the minimum-wage job provides only supplemental income. As the following table shows, even two full-time minimum-wage incomes would barely amount to half of this average.

|

Annual Income Earned for Different Minimum Wages by Hours Worked per Week ($) |

|||

|

$7.40 |

$7.75 |

$8.25 |

|

| 20 hours |

7,696 |

8,060 |

8,580 |

| 34 hours |

13,083 |

13,702 |

14,586 |

| 40 hours |

15,392 |

16,120 |

17,160 |

Notes: The percentages of minimum-wage-earning Rhode Islanders in each hours category is as follows:

Results assume 52 weeks of work per year. Source: U.S. Census, Current Population Survey, 2011 and 2012 |

|||

The following chart illustrates that only a small minority of families rely entirely on a minimum wage income for support, even among households with some minimum-wage income.

What’s the Effect?

We estimate that the increase of the minimum wage from $7.40 to $8.25 per hour will result in a loss of 432 minimum wage jobs in Rhode Island. This total assumes a lower effect on better educated and older workers. That’s a 1.74% reduction of employment available to people currently earning less than $8.25. Of those losing jobs, 204 will be teenagers.

The focus of advocates for higher minimum wages is very often on the plight of people striving to live on such low salaries, but most workers at that pay rate do not fit the profile. Most of them are bringing in relatively small amounts of supplemental income — many as discretionary spending cash for teens and young adults who are still largely supported by their parents.

In the view of the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity, the loss of employment opportunities for Rhode Islanders in this group outweighs the relatively small increases in take-home pay. At young adults’ formative age, the connections, habits, and general experience that come from working at any pay scale are vastly more valuable than the small increases that legislators are able to mandate through minimum wage laws.

At the National Level, a Bigger Hammer

This morning, Rhode Island’s two representatives in the U.S. Congress, Jim Langevin (D) and David Cicilline (D), jointly announced their support for the “Fair Minimum Wage Act.” The act would increase the federal minimum wage — and, therefore, Rhode Island’s minimum wage — to $10.10 per hour.

The RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity estimates that this move would result in a loss of 3,466 jobs for Rhode Islanders, or 4.1% of the total number who currently work at or below that rate of pay. Moreover, even with this broader net, the number of affected families that are subsisting on minimum wage income alone would still be just 17% of all households with at least one member earning that amount.

* Going back to the prior minimum wage rate of $7.40 was necessary because measuring the change from the current rate of $7.75 to $8.25 produced insufficient sample sizes.